Emma R. Alban’s Sapphic Victorian novel, ‘Don’t Want You Like A Best Friend,’ is a charming and witty homage to the classic tales of the genre.

The following interview contains minor spoilers for ‘Don’t Want You Like A Best Friend.’

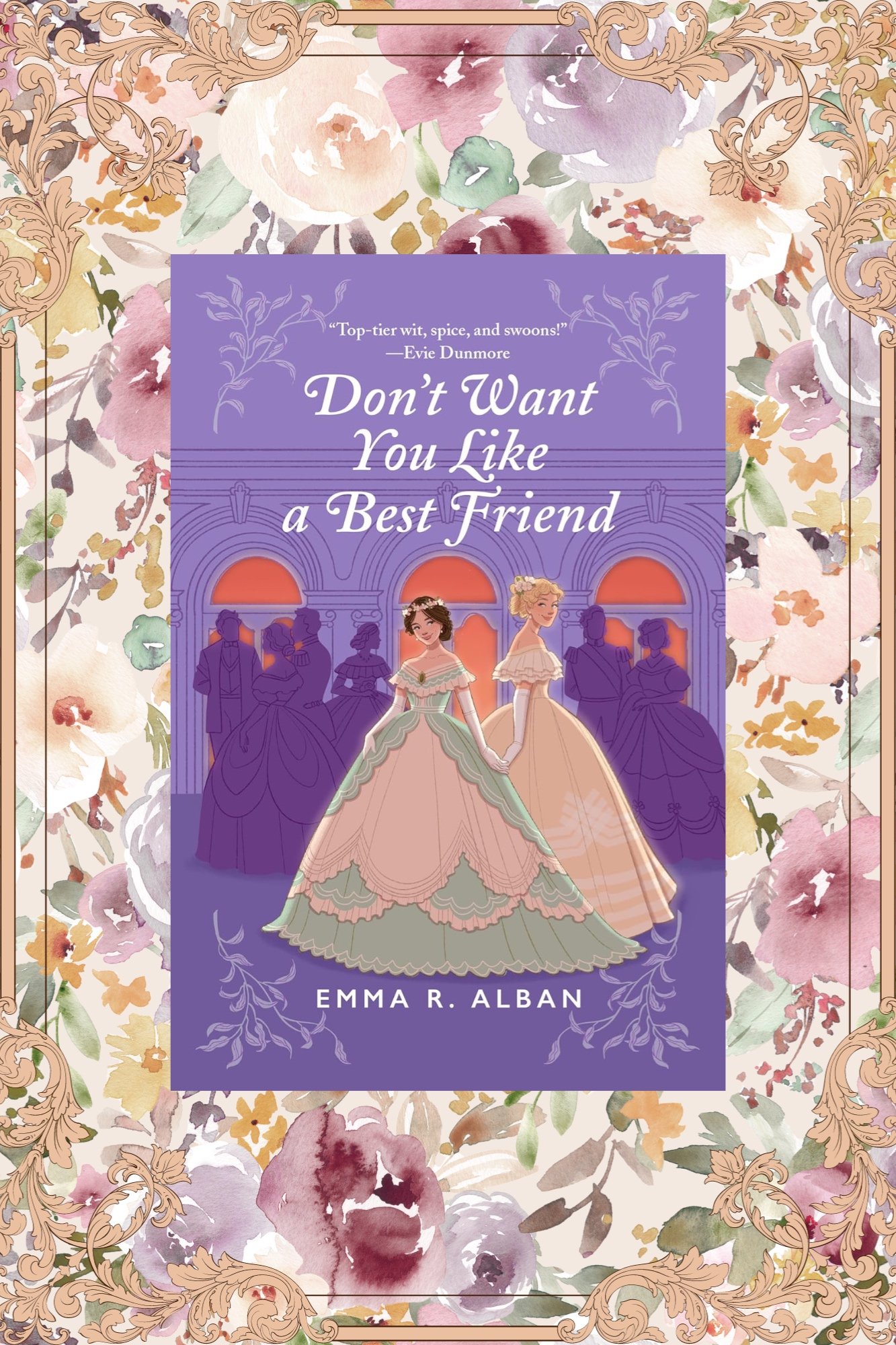

There are a handful of reasons a reader may choose to pick up Emma R. Alban's debut novel, Don't Want You Like A Best Friend. They include but certainly are not limited to the following: It's a historical romance, so for genre lovers, that will be enough. It's queer, so if it's representation you're seeking, look no further. Or, maybe you're like me, and you do very much judge a book by its cover–sorry, not sorry– and are caught in the Leni Kauffman/ Taylor Swift craze that is sweeping the genre and world, respectively. No matter how the book gets into your hands, if you choose to follow through on your purchase, you are guaranteed a quality read. No stranger to stringing words together on a page, Emma is a seasoned and passionate screenwriter and novelist whose love for this genre, her characters, and her community shines through every aspect of her tale (which, yes, is worthy of its title).

Don't Want You Like A Best Friend is a fresh take on a classic and well-adored genre. Mischief, mayhem and the perfect amount of spice round out Beth and Gwen's love story. Bored or marriage mart, the two debutantes soon concoct the ideal distraction: setting up their widowed parents, who seem to be more than the mere acquaintances they claim to be. When the two women realize their feelings for each other are not simply platonic, and it becomes apparent that their parents' pairing is the only way they can ensure their own future happiness, their sideline schemes take center stage. Much as the book's marketing suggests, Alban's debut is the perfect mix of Parent Trap and Bridgerton set in a cozy and comforting world full of loving and colorful characters for which readers will instantly root and with whom they will crave more page time.

Emma took time out of her day to chat with The FMC about how her story came to life, the importance of a corset, the differences between writing for the page and the screen, and more.

Congratulations on Don’t Want You Like A Best Friend! It’s such a unique and charming story.

Thank you!

How are you feeling now that you're fully immersed in press and release activities?

It’s been super exciting. The book has been on a number of really incredible lists, and people are adding it to all these wonderful TBR graphics. I feel so proud and so honored. It's so surreal to see it out there. It's really wonderful. It's been an amazing experience so far.

We obviously have to talk about the title. I think it’s brilliant. It was the hook for me. It’s linked to a Taylor Swift lyric, but it isn’t a song title, so it’s a little sneaky. I know it wasn’t what the novel was originally called. How did it come to be?

We ended up with Don't Want You Like A Best Friend for book one because the second book is called You're The Problem. It's You. That title was totally my publishing team. They came to me, and they were like, “This is what we want to call it.” I was like, “That’s excellent. Yay!” They turned around and said, “We would like a title that matches book one.” I came up with a big list of sapphic-coded Taylor Swift-esque titles, and Don't Want You Like A Best Friend was the last one on that list. The whole team went, “Ooh, that's it.” They had this whole vision. Very specifically, my editor had this whole vision for how it would work and how we would place it, and I think they were 100% right. And the modern title with the historical cover creates a great marketing package. [Laughter] It was a complete team effort. I'm so grateful to them for having such a huge vision for my story.

I think it is the perfect lyric, too, because it really hints at the vibe of the book. When it comes to the story itself, there are obviously some pretty obvious inspirations like Parent Trap and Bridgerton, but what are some other stories that you drew from?

I think the marriage market as a whole, as we see it across all historical books, was a real inspiration. I was really fascinated by how strict it was and the different portrayals of it. For example, you see a season in Jane Austen's books, but they're not in London. It's the difference in the grandeur, but there is still all of the pressure for women to find a match and get married. Another inspiration was reading all of the wonderful historical novels that I have and thinking, “Oh, I could do this, but it could be queer. How fun would that be?” It was both the note of absence and a want to pay homage all rolled into one.

When did you know Don’t Want You Like a Best Friend was the story you were going to write?

I had a book on submission in 2021 that died a very slow death, as they very often do. During that time, I was trying to work on another project. I wanted to write another historical romance. I knew I wanted it to be about an earl and a widowed countess. That was where the seed of the idea came from. But I couldn't figure out why that was interesting. I couldn't come up with a story that I liked for the two of them. Finally, I had the thought, “What if it wasn't their story? What if they both had daughters, and it was their story?” Very quickly, I had plotted that the daughters were queer and it was a parent trap. It came to me very, very quickly and almost fully formed. All I had to do was get to know the characters and all the beats, figuring out how that conflict played out across the whole book. But as soon as I had the idea, I knew the whole story. I don't know that I'll ever have a lightning strike exactly like that again. It was very exciting.

When stories come to you like that, does it feel like you can't get it out of your brain fast enough?

It gives me a big sense of urgency to write, which I enjoy very much.

Something I really enjoyed about the novel was that it falls into the category of historical fiction that is based on real political events, much like Evie Dunmore’s novels. I think it adds a nice sheen of realism to the tale. How did the marriage amendment of 1857 influence your idea in its infancy?

It came secondary to the conceit of the story. When I started outlining everything, I decided I needed to pick a year. I had to pick a place to set this story. When I started looking through the 1800s as a whole, I zeroed in on the 1850s. As I was doing research on 1857, I found that that act, which shockingly, really thematically fit the idea I had in my head. After that, I built them together in tandem. Because so often the season is also the parliamentary season, it created some steps and some structure to how the book would be put together both thematically and in the men's sphere, which we don’t see much of in this book. It helped create some structure, particularly for Dashiell, the dad. Throughout writing the book, the marriage amendment became more and more resident and, in some ways, more and more sad as I went along. It got a lot deeper than I expected. It was fun to get near the end and be like, “Oh, I built that in, okay.” [Laughter]

Knowing that, what was your research process as a whole like for this book?

Before I ever start writing, I'll come up with a concept, and then I will do research on the era or the year I want to put the concept in to make sure I have come up with a concept that actually works. Then, as I do research into that era, it informs how I write the story, much like how the marriage act and the plot mirror each other in this one. I start where I need to for story elements, and then I let that research take me down the rabbit hole. I start with something very general, and then I'll go look at specific references, which take me to JSTOR and more niche articles. Then, I’ll find myself combing through Google Books, looking for highlights. [Laughter] You find surprising things along the way. My approach is more of a rabbit hole situation than it is a structured research situation.

Was there anything you had to go back and change because you realized through your research that it was different than you had thought?

Actually, the hoop skirts!

Oh! That’s such a big part of the story.

I know. When I first started writing, I had them wearing multiple petticoats. As I was doing research, I realized, “Oh, the caged crinoline exists in this period. This is the first year that it was around. Oh, wow, okay.” And that became such a big theme. It was funny to me that it was just a coincidence. As soon as I figured that out, it was like, “This thematically works so well. And then it was going back and rewriting certain sections. As I did research for this book, I learned a lot more about corsetry. I knew the corsetry was never the cage that we think about it as. To all those actresses who are tight-laced: don't be tight-laced! They're functional garments. [Laughter] They were such functional garments. They were so liberating and important for women throughout history, particularly at that time. How I talked about them really evolved throughout the writing process.

With this novel being sapphic, did you know how you wanted to approach it from the beginning in terms of what the characters’ views and prior knowledge were?

I always knew how I wanted all four of the main characters to react. For Beth and Gwen, I didn't want there to be any internalized homophobia. I wanted it to just be, “This is how I think. oh.” I wanted it to be more about discovery for them initially than about what society would think. I intentionally wanted to build in that one of the households was already queer-friendly and that one of the households I had a more societal view that wasn't based on any internal prejudice but in a want to protect the child from the world in a way. I didn't want anyone close to the girls to be the problem. I wanted society to be the problem, and I hope that I was able to keep those layers.

You were, for sure. It was something I really enjoyed about the book. I kept waiting for the classic historical romance proverbial shoe to drop. It was lovely not having to deal with it.

Thank you. Queer people have always been here. While they don't always get written about, they have always had allies and advocates because there wouldn't have been a way forward without them. I did want to explore that as well, the fact that there were families who were supportive, and there have been across history. We just never get to hear about them. They're all going to be supportive in different ways and at different levels. It's not all utopian and wonderful, but they were there.

In your acknowledgments, you mention having been a long-time writer. I know you are also a screenwriter. For you, how are the two types of storytelling different?

The very cut-and-dry answer is one is external, and one is internal. For both, dialogue is my favorite thing. But it prints out so differently on paper than it does on screen. Screenwriting is much more streamlined; the writing is much more utilitarian. The writing is simply in service of making the story visual for the reader and making sure that everything you're doing will play on screen. Meanwhile, when you're writing a book, you have this freedom to explore internal narrative, to take asides and tangents that there's just no page space for in screenwriting, and to describe things in detail. Whenever I'm drafting a novel, I usually do a pass to ensure I actually describe things. That is one of my pitfalls as a screenwriter/novelist. I want to make sure I'm actually taking the time in a book to add in the description because, in a screenplay, all I need to say is, “a Victorian house. There’s ivy.” I enjoy both mediums, and they contain very different challenges. But certainly, the visual and streamlined versus more literary prosaic and internal are the biggest differences.

Being that you do both, have you considered adapting your own novel, or do you have a dream format or cast/crew for a possible adaptation?

I certainly have considered what it would look like on the page. I would love to see it adapted as a TV show. That's my dream. In terms of cast, I don't have anybody super specific that I want to share publicly at this point because if it gets made, whoever is in the role will be perfect for the role. I don't want to prescribe who that should be. To be honest, I actually don't see faces when I write, so sometimes I will pick an actor or an actress to focus on so I have an idea of what my characters look like. I absolutely have an idea of how I would do it. But I would be so excited to see it on screen if it were to get up there.

How do you think the story would need to change for the screen?

It would need to change in that you would broaden the perspective. The novel is very much just from Beth and Gwen's perspectives, and that was very intentional. It is their story. But as you open up a television show, in particular, you have so much more space and time to develop all the other characters. So, I think you'd see a lot more from Dashiell and Cordelia’s perspectives. I would want to build out a lot more of the Albie narrative and have Bobby around a bit more than I got to in the book. I would like to introduce all of the characters and give them all their special moments that you just can't see from one person's perspective.

There's a big world. It's hard when you've got as big of an ensemble cast as you do to give them all enough page time. Speaking of Bobby, It has already been announced that Don’t Want You Like A Best Friend is at least part of a duology, and the next part in the tales does feature in the epilogue. Did you pitch both stories together, or did the second story unfold later on?

Ultimately, I wrote them back to back. When we were pitching Don't Want You Like A Best Friend to editors, I had a pitch for what the next book would be if editors were interested. We were selling Don't Want You Like A Best Friend as a standalone. It had the epilogue that it has the whole way through. Obviously, I could have just ended it there, and readers would know that the chaos went on. But we did pitch that there was a second book. I'm very grateful that Avon wanted to sign on for it, too. Basically, as soon as we finished editing book one, I went straight into writing book two. So not only does book two literally pick up an hour after book one, but that is also very much how the writing process was. They're very deeply intertwined books. It is still a standalone. You can read You're The Problem. It's You without reading Don't Want You Like A Best Friend. I'd suggest you read both. I think it's fun. [Laughter]

I can't wait. If I could have, I would have gone straight into the next one. Lastly, since this is The FMC, which Female Main Character archetype do you relate to most?

The Nerd is my immediate reaction. The Nerd with a Misfit rising would have been younger me [Laughter]. I'd love to think I'll be The Boss someday, but I think The Nerd is where I sit in my heart.